William Frye was a quintessential itinerant portraitist working in the nineteenth-century South. A largely unknown name today, Frye was one of the most successful and prolific painters in Antebellum Alabama. Today, more than 140 of his works have been discovered, the majority of which exist in private collections. Because his paintings were primarily passed down through families rather than placed in public institutions, his works have remained largely unknown.[1] While he created landscapes and Civil War scenes, he was most well-known for his portraits of political figures and prominent Alabama families.

Frye was born in Reslau, Germany in 1822. He immigrated to the United States in 1841 after his education at Heidelberg University. While at Heidelberg, Frye became fascinated with James Fenimore Cooper’s stories of the Native Americans, and journeyed to America to paint them.[2] Frye arrived in New York in 1841. In 1845 he moved to Kentucky, and 2 years later settled in Huntsville, Alabama. While Huntsville was Frye’s home base, he was forced into itinerancy to make a living, traveling throughout Alabama and the surrounding states painting portraits of prominent families. An 1861 advertisement in the Southern Associate reads, “William Frye, artist, has returned home, and will be found in his studio…where he is ready to paint portraits true to life from the original or from daguerreotypes”.[3] Unlike many other artists, Frye had steady commissions throughout the Civil War, painting soldiers departing for battle or returning as heroes. Frye’s success was likely a result of his ability to modify his work to fit the budget of his clients. During the war, Frye reduced his fees by 25% “on account of hardness of times”. [4]

Frye’s portraits are characterized by subjects with wide staring eyes and meticulously detailed clothing and facial features. He avoids backlighting, creating a stark contrast between the pale skin of his sitters and the dark backgrounds. His subjects are typically placed close to the picture plane and fill up the entirety of the canvas, qualities that may stem from his use of daguerreotypes. The use of daguerreotypes influenced both the style and content of Frye’s paintings; he substituted the painterly style of his earlier works for more photographic likenesses, and was able to expand his repertoire to include posthumous portraiture. Frye was rumored to go so far as to paint directly on top of photographs. While daguerreotypes allowed for greater likenesses, they also lead to flatter, stilted compositions in Frye’s later works. [5] Frye’s flat design and bright coloration may have resulted from the influence of the German school, but it is unknown if he ever received classical training.

In an 1870 letter to Dr. Peter Bryce at the Bryce Hospital in Tuscaloosa,[6] Frye’s wife, Virginia, reported Frye’s declining health. After a stroke early in 1870, Frye’s painting skills began to decline; at first, he was conscious of this, but as his symptoms worsened, he insisted that his works were still correct likenesses. In 1871, after another stroke, a spell of vertigo, and a diagnosis of influenza of the brain, Frye was committed to Bryce Hospital. The records state that Frye “gave up his profession a year ago because he could not distinguish colors”[7]. Frye passed away in 1872 after an illustrious, prolific career as an Antebellum Alabama portraitist.

This exhibition focuses on Frye’s individual and family portraiture from 1848-1861. During this period, Frye experienced the most financial success and produced his most highly regarded work. The goal of this exhibit was to document his work as a portraitist before his sudden decline in skill due to health issues and mental instability.

Sarah Louise and Mary Goodloe, c. 1856. Oil on canvas, 46″x36″. Collection of Mrs. Walter E. Morris.

The sisters sit together on a red velvet bench against a dark landscape. They are dressed alike, in white, off-the-shoulder dresses and matching pantalettes. Their pale skin is highlighted against the dark background, a common trait in Frye’s work. Mary sits in the front, with a rose-colored sash, holding a hat decorated with roses. Sarah Louise sits behind her sister, placing her hands tenderly on her sister’s shoulders. The patron, Mrs. Goodloe, valued this portrait immensely, saying in a letter to her daughter, “I would not take a million for the picture”.[8]

The Goodloe Children, c. 1858. Oil on canvas, 50″x39″. Collection of Mrs. W. T. Goodloe Rutland.

2 years after painting Sarah Louise and Mary Goodloe, Frye returned to paint three other children in the family. The Goodloe Children is a romantic picture of three children playing on a bridge over a body of water. Susan sits between her two brothers and holds a woven basket. Bobbie (Robert), left, rolls up his pant legs, as if preparing to play in the water. Jimmie (James), right, already has one foot in the water and holds what might be a fishing rod. Mrs. Goodloe requested that the boys be shown playing by a creek, but also gave artistic license to Frye, saying in a letter to Sarah Louise, “I think [it] will be best probably to leave it to him altogether, as we did when he took yours and Sis’s portrait”.[9]

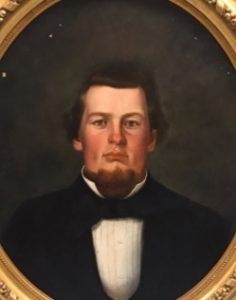

Captain Frank B. Gurley, 1864. Oil on linen, 30″x25″. Huntsville Museum of Art.

The portrait of Frank B. Gurley is a standard Civil War portrait. The confederate soldier is shown in his uniform. Gurley was the leader of a guerilla rebellion against the Union. Gurley was imprisoned from 1863-1865, during which time this portrait was painted. Knowing this, it is likely that Frye painted Gurley’s portrait from a daguerreotype.

Andrew Drake, c. 1855. Oil on fabric, 30″x25″. Huntsville Museum of Art.

Andrew Drake was an early settler of Huntsville, the area of Alabama where Frye spent the most time.[10] For generations, his family owned land in the area now known as Jones Valley. Here, he is shown wearing a black jacket over a grey vest with a white pleated shirt. His black kerchief is tied loosely around his neck.

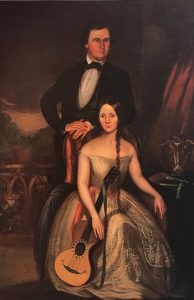

Minor Winn Gracey and his wife, Mourning Smith, 1851. Collection of Mr. William M. Spencer.

In one of his more elaborate and well-known portraits, Frye places the Graceys against a background of the hills of Marengo County. The Graceys lived in the historic Waldwic Plantation, which Minor inherited from his father.[11] This portrait is a celebration of not only Gracey’s, but of the planter class’s wealth and status. Frye was known to adjust the detail of his works to fit the budget of his clients. Here, the exquisite detail can be seen in the beading on Mourning’s dress, in the mandolin she holds, and the decorative vase on the table. This work is an example of Frye’s earlier portraits, when his portraits were more painterly than they were photographic likenesses.

Alexander Keith Marshall McDowell, 1850. Oil on Canvas, 33″x28″. Huntsville Museum of Art.

The portraits of Alexander and Anna McDowell are considered to be some of Frye’s best. Both are in excellent condition and have a clear provenance. [12]

Anna McDowell, 1850. Oil on canvas, 30.5″x25″. Huntsville Museum of Art.

This portrait of Anna McDowell is the pendant to the portrait of Alexander Keith Marshall McDowell. These portraits exemplify Frye’s ability to capture his subjects in a ‘live’ sense; their likenesses are so detailed that the viewer feels as if they are in the room with them.

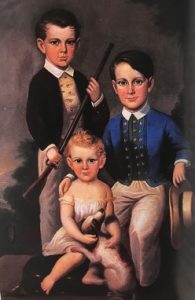

William Patton, James, and John Patton Richardson, c. 1856. Oil on canvas, 50″x45″. Collection of Mrs. Sam Davis Bell.

This portrait features William Patton, James, and John Patton Richardson, three of the six children of Edmond Richardson and Mrs. Richardson (Margaret Patton). Richardson was one of the South’s foremost cotton planters, and his wife Margaret Patton was the sister of Alabama’s 20th governor, Robert Patton.[13] The wide, staring eyes characteristic of Frye’s work are especially prominent here. The youngest child holds a pet dog. In Antebellum portraiture, children were frequently portrayed with animals.

Robert Nashville Malone, c. 1861. Oil on canvas, 29″x24″. Huntsville Museum of Art.

Malone was a planter in Madison County, Alabama. This is a traditional portrait by Frye. He captures small details about the sitter’s appearance, such as the small dimple on the left side of his face that results from his slight smile.[14]

Miss Ellie Lowe, 1858. Oil on canvas, 39″x29″. Huntsville Museum of Art.

In this portrait, Miss Ellie Lowe is shown in an idyllic setting. The sun sets in the landscape behind her, and she is surrounded by vines and flowers. Her arm rests on a square pillar with an urn or vessel on top. Her hair is worn in a traditional up-do, and her white off-the-shoulder dress features lace and pearl detailing. Frye’s works were typically done against plain backgrounds or very dark backgrounds with minimal detail; the fact that this portrait has a more detailed sky and foliage suggests that the Lowe family could afford a higher-priced portrait.

Frye’s portraiture, despite its lack of recognition today, was some of the most highly regarded of the Antebellum period. Despite the known existence of over 140 portraits by Frye, the majority are in private collections, passed down through families. Until more of his works are available for public study, it is difficult to fully understand the range of his portraiture. Like many painters of the American South, research on Frye is limited due to scarcity of record. What is known is that he was one of the most prolific painters of Antebellum Alabama, and he is responsible for documenting hundreds of prominent Alabama citizens.

[1] E. Bryding Adams, “William Frye, Artist,” Alabama Heritage 32 (Spring 1994): 30.

[2] Coleman, Minnie F. “Minnie Frye Coleman Writes Her Father’s Story”. Huntsville Musem of Art Archives. Huntsville, AL.

[3] Women’s Guild of the Huntsville Art League and Museum Association, Three Painters from Old Huntsville (Huntsville, AL), 2.

[4] Black, Patti Carr. Art in Mississippi, 1720-1980. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

[5] E. Bryding Adams, “William Frye, Artist,” Alabama Heritage 32 (Spring 1994): 32.

[6] Virginia Frye to Dr. Peter Bryce. Winter 1870. Huntsville Museum of Art Archives. Huntsville, AL.

[7] Virginia Frye to Dr. Peter Bryce. Winter 1870. Huntsville Museum of Art Archives. Huntsville, AL.

[8] E. Bryding Adams, “William Frye, Artist,” Alabama Heritage 32 (Spring 1994): 36.

[9] E. Bryding Adams, “William Frye, Artist,” Alabama Heritage 32 (Spring 1994): 36.

[10] Cunningham-Adams Fine Arts Painting Conservation, Conservation Treatment Report: Portrait of Andrew Drake, July 26, 1994.

[11] Jennifer Hale, Historic Plantations of Alabama’s Black Belt (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2009).

[12] Appraisal Report: Alexander Keith Marshall McDowell and Anna McDowell.

[13] E. Bryding Adams, “William Frye, Artist,” Alabama Heritage 32 (Spring 1994): 36.

[14] Alabama Portraits Prior to 1870 (The Historical Activities Committee), 226.