Bonaventure Cemetery is one of the oldest and most famous cemeteries in Savannah, Georgia. Its name derives from the Italian saying, buona ventura, meaning “good fortune” [1]. The land Bonaventure is located on was once the plantation homes of the Tattnall and the Torrey family. The Tattnall family plantation was built in the 1760’s alongside the Wilmington River.[2] In 1846 Commodore Josiah Tattnall sold 600 acres of the estate to Peter Wiltberger. Wiltberger wanted to turn seventy acres of the property into a cemetery but he died before achieving his dream.[3] His son William was able to fulfill his father’s dream, however in 1868 William Wiltberger converted the property into Evergreen Cemetery [4]. After William Wilberger’s death, the cemetey’s titles passed to the Evergreen Cemetery Company. Evergreen Cemetery soon began to be known as Evergreen Cemetery of Bonaventure. In 1907 the City of Savannah bought the cemetery, and the sight which had become known as Bonaventure was able to accommodate more graves.

The remaining property that Bonaventure eventually expanded into was known as Greenwich Plantation. Greenwich plantation has a complicated history. Not much is known about its origins or which families owned the land. The most famous tenant of Greenwich was Dr. H.N. Torrey of Detroit, who purchased the land in 1917.[5] Dr. Torrey’s Greenwich was said to be the most beautiful private home in the South. In its prime, movies were filmed at the house and lavish parties were thrown.[6] In 1923 the house burned to the ground and the property was abandoned until 1937 when the city of Savannah purchased the land and expanded Bonaventure Cemetery.[7]

Bonaventure is a classic example of a Victorian Cemetery, and it reflects the changing views on death in Victorian society [8]. Victorians began to romanticize death and cemeteries were no longer a place of sadness. Cemeteries began to look like parks and became a place of rest for the dead as well as a place of relaxation for the living. Bonaventure became a city of the dead, rather than just a place of burial.[9] Many of Bonaventure’s graves date to the Victorian Era and are decorated with iconography that was typically depicted on headstones during the era. The symbolism on the headstones each represent something different, and were chosen because they were considered meaningful by the deceased and their family. I argue that specific graves in Bonaventure Cemetery reflect society’s need to find comfort in death, conveyed through their choice of headstones and grave markers. The grave markers I will be focusing on are statues of the deceased, angels, epitaphs, and tombs. Statues of the deceased convey the sense of loss felt by the families and the need to preserve the memory of the deceased. Angels were used to show the deceased was safely accepted into the heavenly afterlife. The epitaph was used to distinguish and give insight into the deceased’s personality and tombs represent “houses of the dead” that were utilized for the families of the dead to find comfort. The iconography depicted on gravestones from the Victorian Era gives insight into Victorian views on death and their need to preserve the memory of lost loved ones.

[1]Eva Barrington, “Bonaventure, Savannah’s “Silent City””, The Georgia Review, 5, no.3 (1951): 300-304

[2] Ibid.

[3] Mandi Dale Johnston and Aime Marie Wilson, Historic Bonaventure Cemetery (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 1998), 17.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, 50.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid, 62.

[8] Ibid, 28.

[9] Ibid.

Figure One: Grave marker of Corinne Elliott Lawton Sculpted by Benedetto Civiletti, 1879, Sicily Italy. (From: Michael Karpovage, “Bonaventure Burial: Corinne Elliot Lawton” Savannah.com, Savannah.com)

Corinne Elliott Lawton was a local Savannah woman and the daughter of Confederate Brigadier General Alexander Lawton. She died at the young age of 31 and her family’s grief was great. To ease their bereavement the Lawton family had the exact likeness of their daughter immortalized in the form of a statue (fig.1).[1] Nineteenth century Americans had a reluctance to “let go of the dead” and statues made in the likeness of the deceased were created to preserve the memory of the dead[2]. Grave markers that contained the likeness of the deceased were typical of the Victorian era. Victorian’s wanted to preserve the memory of the dead by being able to come to the grave sites and physically see something the resembled the family member that passed. Families of the deceased found comfort in the immortalized marble likenesses of the deceased, reassuring them that their dead family member was still with them in memory.

The grave marker of Gracie Watkin’s is another example of Victorian families attempting to preserve the memory of their deceased loved one. (fig. 2). Gracie Watkin’s grave is one of Bonaventure’s most famous and most visited grave sites. It marks the grave of a young girl who died in Savannah in 1889. Gracie’s parents owned a hotel in Savannah, and she was known in life for her sweetness.[3] Gracie’s parents were in an immense amount of pain at the death of their young daughter and wanted something to forever remember her by. According to legend Gracie’s statue closely resembles her in life. She is depicted wearing a dress that she was commonly seen wearing.[4] Her parents attempted to recreate what their daughter looked like in life, to find comfort in her death. Statues are representative of what an individual had looked like in life. Statues with the exact likeness of the deceased are common in Bonaventure Cemetery because it allows families of the deceased to visit a lost loved one and feel as though they are still physically with them.

Figure Two: Statue of Gracie Watkins. Digital Image. (From: Pam DeCamp Photography).

The graves of children were often marked with statues, though, they were treated differently than adult graves that were marked with statues. The Victorians saw children as innocent and uncorrupt beings in life and the same view was carried on into death.[ 5]

5]

[1] Ibid.

[2] James Hijiya, “America Gravestones and Attitudes toward Death: A Brief History”, Proceedings of the America Philosophical Society, 127, no.5, (1983): 339-363.

[3] Mandi Dale Johnston and Aime Marie Wilson, Historic Bonaventure Cemetery, 104.

[4] Ibid, 105.

[5] Ellen Marie Snyder “Innocents in a Worldly World: Victorian Children’s Grave markers”. In

Cemeteries Gravemarkers, edited by Richard E. Meyer, 11-28. Boulder: University Press

of Colorado, 1989.

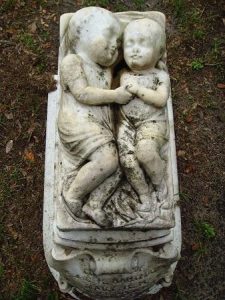

Figure Four: Empty Beds. Digital Images. (From: Google Images).

Sculptural representations were often realistic in appearance and size reinforcing the need to preserve the deceased’s memory. The most common depiction was that of the sleeping child (fig. 3). [1] This was representative of the innocence associated with children and the need to find comfort in the death of a child. Showing the child sleeping it would give comfort to the grieving family, that their child was simply in an eternal slumber.[2] Empty beds were also commonly used as grave markers for children and are representative of children’s unfulfilled lives (fig.4).[3] Empty beds were a way for parents to cope with the loss of their children and accept their premature death.

Victorians needed a way to cope with the loss of their loved ones so they would choose a grave marker that was in the likeness of the deceased. In the sculptural representations, the family found comfort knowing that the dead were still with them in visual form.

[1] Ibid.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

Sculptural representations were often realistic in appearance and size reinforcing the need to preserve the deceased’s memory. The most common depiction was that of the sleeping child (fig. 3). [1] This was representative of the innocence associated with children and the need to find comfort in the death of a child. Showing the child sleeping it would give comfort to the grieving family, that their child was simply in an eternal slumber.[2] Empty beds were also commonly used as grave markers for children and are representative of children’s unfulfilled lives (fig.4).[3] Empty beds were a way for parents to cope with the loss of their children and accept their premature death.Victorians needed a way to cope with the loss of their loved ones so they would choose a grave marker that was in the likeness of the deceased. In the sculptural representations, the family found comfort knowing that the dead were still with them in visual form.

Figure Five: Sleeping Cherubs. Digital Image. (From: The Tombstone Tourist). November 22, 2014.

[1] Ibid.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

Angels were also a common grave marker used in Bonaventure Cemetery. In Victorian belief, angels were representative of heaven. [1] Choosing an angel as a grave marker was a way for the family to choose a grave marker that would essentially protect the deceased and help ferry them into the afterlife. Angels could be depicted as divine begins or simply a human face with wings.[2] Image five is a grave marker adorned with two cherubs. The grave marker states that it is the graves of two children. The cherub could have been used as a part of the marker because a cherub is representative of children. Angels were also depicted as divine beings. Having an angel as a grave marker gave the family of the deceased comfort that the dead were in a better place. Angels represented a savior to the Victorians, and were a recognizable and familiar sculptural representation.

[1] James Hijiya, “America Gravestones and Attitudes toward Death: A Brief History”

[2] Ibid.

This angel marks the graves of the two wives of Francis Ruckert. Ruckert was a prominent saloon owner in Savannah. The date his first wife died is unknown. His second wife Louisa died in 1893 and was put to rest next to her predecessor. [1]

[1] Ibid.

John Waltz designed the head stone for husband and wife, Joseph and Clara Herschbach. The headstone was carved in a Grecian style with the angel being flanked by two ionic columns[1]. On the bottom of the grave there is a symbol of the CSA. Joseph Herschbach was fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War.[2]

[1] Ibid.

[2] Mandi Dale Johnston and Aime Marie Wilson, Historic Bonaventure Cemetetery, 103.

The epitaph was used to help memorialize the dead and find comfort in their passing. It can be argued that the epitaph serves as an important part of society that gives insight into the personality of the deceased and their living loved ones.[1] The epitaph can also evoke images of the deceased as well as personality traits that characterized them in life. [2] One of the most common types of epitaphs are short verses. Verses tend to express grief or state that the deceased have passed on to a better world.[3] All three epitaphs indicate the passing of a loved one into a better place.

The first epitaph I analyzed is on the pedestal of the grave of Corinne Lawton, stating, “Allured to brighter worlds and led the way”. This line is from the poem The Deserted Village by Oliver Goldsmith, which is about the loss of life.[4] The line states the dead was lured to a world that is a better place than earth. The line “led the way” could mean the dead was being ferried to another world by a divine being. The epitaph is paired with the life like statue of Lawton, and it functions in a similar way, to preserve the memory of Lawton. After her passing, Lawton, was “allured to a brighter world”. This verse was intended to give the family comfort in the passing of their daughter, because she has passed to a world that is better than the Earthly realm.

The second epitaph is from Romans 15:13, stating, “The God of Hope fill us with all joy and peace in believing”. The verse is utilized as a comforting saying in the face of death. The quote refers to “us” meaning that not only the dead will find comfort in death but the family of the deceased will as well. Epitaph three states, “Bless the Lord oh my soul”. The verse is from Psalm 103:2, and is a short plea of the hope that the dead will be safely harbored into the afterlife[5]. The family of the dead also found comfort in the verse because it assures them that the deceased will be safe after journeying to the afterlife.

Victorian cemeteries had become cities for the dead and tombs had become houses for the dead. Generations of families were buried within the vaults, functioning similarly as family homes had in life. The Mongin-Stoddard Tomb housed the remains of the Mongin and Stoddard families. John David Mongin, the most notable family member, owned and operated the first steamboat that went between Savannah and Charleston.[6] The family was originally buried at their ancestral property on Daufuskie Island but in 1875 were moved to Bonaventure.[7] The Mongin-Stoddard tomb acts as house of the dead for the family keeping the remains together for eternity. The Gaston Vault, also known as the Strangers Vault, is located at the entrance of Bonaventure[8]. The Gaston Vault was built as a memorial to William Gaston, a Savannah merchant who was known for his hospitality to strangers.[9] Locals collected donations after Gaston’s death to help build a tomb in his honor. The tomb functioned as a temporary resting place for strangers who died in Savannah though, Gaston’s remains currently rest in the vault.[10] Gaston’s Tomb is representative of southern culture in life and death. Even in death, Southerners proved to be just as hospitable as they were in life. Gaston Vault and the Mongin-Stoddard tomb both convey how Bonaventure cemetery became a place for families to remember and find comfort in the loss of the dead.

The land that Bonaventure Cemetery was built upon originated as the plantation homes of two of Georgia’s earliest and most prestigious families located along the serene Wilmington River. Bonaventure and Greenwich once were houses for the living full of life and splendor. Now, the houses no longer stand, and the land has become the final resting place for the dead. Bonaventure is a typical Victorian cemetery equipped with iconography that conveys Victorian beliefs about the afterlife. Each graver marker in Bonaventure conveys the family of the deceased’s need to find comfort in the loss of their loved ones. Families would select statues that showed the exact likeness of the deceased, angels, epitaphs, or tombs, to preserve the memory of the deceased for eternity.

[1] J. Joseph Edgette, “The Epitaph and Personality Revelation”. In Cemeteries Gravemarkers, edited by Richard E. Meyer, 87-101. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1989.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Oliver Goldsmith, The Deserted Village, The Book of Georgian Verse (New York: Brentanos 1909).

[5] The Bible. New International Version, Biblica International, 2011.

[6] Mandi Dale Johnston and Aime Marie Wilson, Historic Bonaventure Cemetery, 71.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, 98.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

Bibliography

Barrington, J. Eva. “Bonaventure, Savannah’s “Silent City””. The Georgia Review, 5, no.3

(1951): 300-304. JSTOR.

Edgette, Joseph. “The Epitaph and Personality Revelation”. In Cemeteries Gravemarkers, edited

by Richard E. Meyer, 87-101. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1989.

Goldsmith, Oliver. The Deserted Village: The Book of Georgian Verse. New York: Brentaos,

1909.

Gorman, J.E. Frederick and DiBlasi, Michael. “Gravestone Iconography and Mortuary

Ideology”. Ethno history, 28, no.1 (1981): 79-98. JSTOR.

The Holy Bible, New International Version. Biblica International, 2011.

Hijiya, James. “American Gravestones and Attitudes toward Death: A Brief History”.

Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 127, no.5 (1983): 339-363. JSTOR.

“History”. Bonaventure Historical Society. Bonaventure Historical Society. Accessed September

15th, 2017. http://www.bonaventurehistorical.org

Snyder, Ellen Marie. “Innocents in a Worldly World: Victorian Children’s Gravemarkers”. In

Cemeteries Grave Markers, edited by Richard E. Meyer, 11-28. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1989.

Wilson, Amie Marie, and Johnston, Dale Mandi. Historic Bonaventure Cemetery. Charleston:

Arcadia, 2000.