George Rodrigue- a Retrospective

Introduction:

George Rodrigue is most known today as the artist of the Blue Dog. While Rodrigue gained fame and fortune for his Blue Dog works, the series that made him a name in the art world has overshadowed his earlier and perhaps more accomplished works. Rodrigue’s earlier evangelical and landscape paintings show his love for the Louisiana setting and inherent Cajun culture. Sadly, these works that show Rodrigues personal relationship with his homeland have been surpassed by the Blue Dog. This exhibit plans to explore Rodrigues less commercially recognizable work and gain insight to his love of the state of Louisiana as his inspiration in his works.

Rodrigue was born March 13, 1944 in New Iberia, Louisiana.[1] His father was of true Acadian descent, a culture that traveled from France to Nova Scotia then Louisiana, settling in the Bayou.[2] His mother was of purely French heritage.[3] It was during his long drives to and from art school in Los Angeles, passing through many states and different landscapes that made Rodrigue realize how unique the low-lying Louisiana landscape was.[4] He began his first series depicting the swamp landscape and oak trees.[5] When Rodrigue would work in a series, he imbued every work he created with the same unifying element; his first being the oak tree. Interestingly, Rodrigue deliberately failed to picture the lands of the Bayou as a warm and inviting environment. His landscapes are often dark, with the most light coming from far off the horizon, the large oak trees moss hanging down forebodingly. Later, his works advanced to use his fellow Cajuns as the subjects of his series. Rodrigue saw his Cajun culture and people diminishing, much like the actual swamplands.[6] The Cajuns were not modernizing with the times and their culture was dying out. If it weren’t for Rodrigue’s depictions of Cajun cultural activities, history might have forgotten the Cajun people. In his paintings of the Cajuns, Rodrigue has said he never pictured them standing; they were always sitting to symbolize how they are a non-progressive people that would never leave the Bayou they inhabit.[7] Rodrigue’s second series, The Evangeline, stemmed from the Cajun tale of the Evangeline who haunted the bayou.[8] She is somewhat of a symbol to the Bayou people for her patient suffering, as the Cajuns have gone through many hardships as a people.[9] His last series, one which he worked in until his death on December 14, 2013 was the Blue Dog series.[10] The Blue dog series started with inspiration from Cajun tales, depicting Loup- Garou, a dog that haunted the Louisiana swamps.[11] Even though the Blue Dog was created out of Cajun folklore, it has grown so commercialized it has lost its Cajun identity.

Rodrigue may have saved his Cajun culture from being erased in the history books, but he also shed a light on the culture with his arts. During his 1976 exhibition in Boston, the Cajun culture was so unknown that he was introduced as a “ka-yoon” artist.[12] Today, most Americans know of the Cajun culture prevalent in Louisiana and the South.

All Rodrigue’s works, from his earliest landscapes to the Blue Dogs, share one characteristic; they have some type of Cajun bayou influence. His earlier landscapes and images of Cajun people display a culture that is once again overshadowed. This project intends to reemphasize the works that made Rodrigue successful that have been somewhat forgotten today.

Bibliography

Bernard, Shane K. The Cajuns: Americanization of a People. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2003.

Danto, Ginger. The art of George Rodrigue. New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 2003.

Fruendlich, Lawrence S. and John Bradshaw and George Rodrigue. George Rodrigue: A Cajun Artist. Washington, D.C.: Studio, 1997.

Rodrigue, Wendy W. The Other Side of the Painting. Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2013.

Rodrigue, George and Floyd Sommier. The Cajuns of George Rodrigue. Birmingham, Alabama: Oxmoor House, 1976.

Rodrigue, George. Le Petit Cajun: Conversations with Andre Rodrigue. Winter Park, Florida: Legacy Publishing, 1978.

Figure 1: Broken Limb, 1975. Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 inches. Private Collection.

Rodrigue began his series on Oak Trees after witnessing the landscapes of other states as he drove to and from Los Angeles where he attended art school.[13] He saw once he entered Louisiana, the land became flat, wet and dark as the massive oak trees blocked the sun.[14] This made Louisiana uniquely different than all other states he had passed through.[15] A recent graduate of art school, studying pop art, Rodrigue was inclined to paint the landscapes he saw with hard edges and a more abstract style.[16] Rodrigue said he never ‘saw’ an oak tree, but noticed the shapes the light created as it passed through the branches. [17]

Rodrigue chose to depict the landscapes of his beloved homeland as so dark and foreboding as a symbol for Louisiana.[18] The people were strong and dominating, as paralleled in his strong oak trees. His landscapes tried to capture the idea of ‘Old Louisiana’, a place where the people were one with the land, connected to their roots.[19] Rodrigue is noted as saying “Every great artist has taken a common thing and made people see it in a different way”.[20] Rodrigue took the common scenery of Louisiana and made the viewer notice not the tree, but the strength of the tree itself, seen through its branches and emanating light. The landscapes that made Rodrigue realize how Louisiana was different from the rest of the country then advanced to show how the customs, traditions and people of Louisiana were different.

Figure 2: Sugar Bridge over Coulee, 1973. Oil on canvas, 48 x 72 inches. Private Collection.

Sugar Bridge over Coulee depicts a landscape in Louisiana.[21] These scenes are typical landscapes Rodrigue was painting when he returned home from art school in California and recognize the unique landscape Louisiana landscape. Evident in this painting is the dark scenery the large oak trees created. This composition of the light source coming from the back ground became one of Rodrigue’s signature elements.

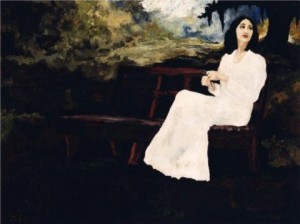

Figure 3: Evangeline Park Bench, 1976. Oil on Canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Private Collection.

Rodrigue worked throughout his career on the Evangeline series, never stopping to begin work on another series like he did the Oak Trees and Cajun People.[22] These works were inspired by Evangeline, who was an Acadian (during the time the culture lived in Nova Scotia) heroine.[23] Folklore stories claim that Evangeline and her lover were separated when the British invaded Nova Scotia in 1755.[24] The lovers were separated as the Acadians went south to the Louisiana Bayou.[25] She searched the bayou corner to corner, looking for her lost lover.[26] The pair were reunited in the last minutes of his life as she cared for him.[27] The tale is common among the Arcadian culture as one of persistence and heartbreak. [28]

The Evangeline works, like all of Rodrigue’s series, take a common form. One figure, the Evangeline, is portrayed. She wears lighter colors and is surrounded by the landscape of the bayou. She is caught in scenes of somberness, lonely, waiting to be reunited with her lover.

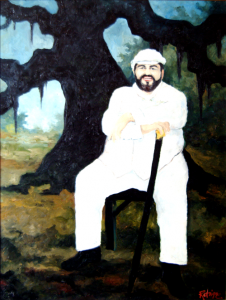

Figure 4: Paul Prudhomme, 1986. Oil on Canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Collection K-Paul’s Louisiana Kitchen, New Orleans.

Figure 4: Paul Prudhomme, 1986. Oil on Canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Collection K-Paul’s Louisiana Kitchen, New Orleans.

Rodrigue’s portrait of Chef Paul Prudhomme commemorated the 1986 opening of the Chef’s restaurant in New York City (now closed).[29] Rodrigue painted three portraits of Prudhomme over his career, as the two were longtime friends.[30] Rodrigue and Prudhomme shared many similarities. They were both from Acadia Louisiana neighborhoods, both influenced in their works by their Cajun culture, and both brought spotlight to their culture with their work.[31] In this portrait, Rodrigue depicts chef Prudhomme as attached to the Louisiana swamplands, a typical style for which he depicts his Cajun people. Prudhomme is dressed in all white, another element typical of Rodrigue’s Cajun portraits. An oak tree and little light from the landscape complete the painting in distinctive George Rodrigue fashion.

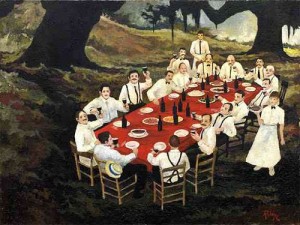

Figure 5: Aioli Dinner, 1971. Oil on canvas, 32 x 46 inches. Collection the Ziegler Museum, Jennings, Louisiana.

Figure 5: Aioli Dinner, 1971. Oil on canvas, 32 x 46 inches. Collection the Ziegler Museum, Jennings, Louisiana.

Rodrigue’s works on Cajun people came about as a remembrance for the old Cajun culture which was disappearing even in the Acadian populated Bayou.[32] The old Cajuns were a people stuck in the past. Rodrigue painted them just as he saw them, wearing older clothing, doing tasks they would normally be doing.[33] As he painted stories from the past, he used his own memory or folklore tales popular to the Cajuns as inspiration.[34] For this painting in particular, Rodrigue painted from a photograph.[35] The scene was an old family dinner from when Rodrigue was a child.[36] These dinners were commonly called Creole Gourmet Dinner society meals, where groups of men would gather at one house and be served for hours by their wives and children.[37] It shows his whole extended family where only the men eat the meal the women provided, as the young children serve.[38] The Aioli People was Rodrigue’s first painting away from the oak tree series but some of the style he developed while creating landscapes carried through to his depiction of people.[39] As he did in his landscapes, Rodrigue had sunlight as coming from behind the scene. The scenes he paints are not illuminated with light; rather they are a placement of dark figures on a dark landscape. This method may tell the viewer that the scene they are witnessing is from the past, the characters ghost-like on the dark landscape, reminding the viewer that this old Cajun lifestyle is gone.

Figure 6: Gourmet Club, 1978. Oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Collection the University of Louisiana, Lafayette.

Figure 6: Gourmet Club, 1978. Oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Collection the University of Louisiana, Lafayette.

This later painting of a gourmet dinner was done after Rodrigue’s first, The Aioli Dinner, received critical acclaim.[40] In these later gourmet dinner works, Rodrigue adds more color and makes the scene more inviting with his positioning of the figures, welcoming the viewer in a toast. A custom of the dinner society was for the male diners to each bring their own bottle of wine, as seen with the many bottles on the table.[41] Overall, these later dinner scenes are more inviting to the viewer but contain the typical George Rodrigue formation of oak trees, figures in white and little sunlight.

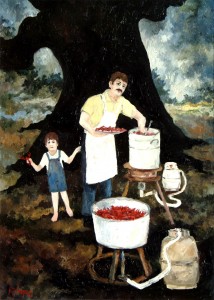

Figure 7: Andre and Boudreaux boiling crawfish, 1978. Oil on canvas, 24 x 18 inches. Private Collection.

Figure 7: Andre and Boudreaux boiling crawfish, 1978. Oil on canvas, 24 x 18 inches. Private Collection.

This painting is a more typical Rodrigue Cajun scene. In these Rodrigue works, the figures are caught in the midst of their everyday Cajun lifestyle.[42] Again, the figures are depicted in stark light colors in contrast to the dark landscape. Rodrigue chose to depict his people normatively for their culture to preserve the lifestyle they lead.[43].

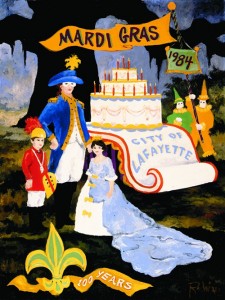

Figure 8: Mardi Gras, 1984. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches. Private Collection.

Mardi Gras was commissioned in commemoration of the city of Lafayette, Louisiana’s, 100 year celebration of the Mardi Gras festivities.[44] The most interesting aspect to this painting is that Rodrigue chose to position the Mardi Gras old revelers in the Bayou, surrounded by his distinctive oak trees. This scene shows classic Cajun culture in the celebration of Mardi Gras, present in Rodrigue’s typical setting.

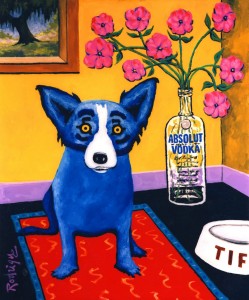

Figure 9: Watchdog, 1984. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches. Private Collection.

In 1980, Rodrigue was commissioned to illustrate a book on bayou ghost stories.[45] Rodrigue was to create forty images to go along with the book, all of which he made on canvas.[46] For the tale of the dog-wolf that haunted the bayou’s graveyards, Loup- Garou (in French directly translated to werewolf), Rodrigue used the likeness of his deceased dog Tiffany.[47] Rodrigue maintained that his choice of Tiffany for the shape of Loup-Garou was only by chance as he had many pictures of her around, and in no way was Watchdog meant to be a commemorative piece to Tiffany.[48] The choice of blue to depict Loup-Garou was also by chance. Rodrigue wanted a color to pop out from the grey tones of the stone Loup-Garou sits atop.[49]

Today, the blue dog is thought to have been an overnight sensation. Contrarily, after Rodrigue’s commission with the ghost book, he continued to paint the blue dog.[50] He was “haunted by it”.[51] In works following the first blue dog, Rodrigue would paint the dog alone in the bayou, in place of a Cajun person or an oak tree. The blue dog became his new model, the new subject of a series. Similar to what Andy Warhol did with the Campbell’s soup can, Rodrigue’s blue dog images became a cultural phenomenon. The Blue Dog gained national attention when it was seen on an advertisement for Absolut Vodka in 1993, even though Rodrigue himself stopped drinking alcohol, and when he did it was “always whiskey”.[52] With the success of the blue dog, Rodrigue started to create prints of his image.[53] Today, there are multiple ‘Blue Dog’ cafes, run by Rodrigue’s son.[54] The Blue Dog has been about everywhere and done about everything, from his yearly Mardi Gras commemoratory prints to prints raising money for a natural disaster. Rodrigue’s legacy in the art world will be the blue dog, just as Warhol’s legacy will be soup cans.

Figure 10 : Absolut Rodrigue, 1993. Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 36 inches. Collection Absolut Vodka.

The aforementioned Absolut advertisement campaign featuring the blue dog, which brought Rodrigue and his blue dog series fame.

Conclusion:

While George Rodrigue is known today for his art, it remains to be seen if he will be remembered and studied for his art. Rodrigue stands with other famous artists like Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp who took an idea and commercialized it, translating the blue dog to something the public as a whole recognized. Before his big break with the blue dog, Rodrigue was known to Louisiana and the South as a Cajun painter. The blue dog, although it stemmed from Cajun tales, has today lost its cultural identity, instead being swept up by the commercial art economy. Sadly, Rodrigue’s earlier landscapes and Cajun paintings were left off the pages of art history books and off the walls of major museums. Rodrigue died in December of 2013 without seeing his works, blue dog or otherwise, critically praised or adorning the walls of a major art museum collection.

[1] Ginger Danto, The art of George Rodrigue (New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 2003), 250.

[2] Shane K. Bernard, The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), 37.

[3] Ginger Danto, The art of George Rodrigue (New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 2003), 17.

[4] Ibid., 25.

[5] Ibid., 25.

[6] Wendy W. Rodrigue, The Other Side of the Painting (Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2013), 7.

[7] Ginger Danto, The art of George Rodrigue (New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 2003), 11.

[8] Wendy W. Rodrigue, The Other Side of the Painting (Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2013), 15.

[9] Ibid., 15.

[10] Ginger Danto, The art of George Rodrigue (New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 2003), 250.

[11] Ibid., 34.

[12] Wendy W. Rodrigue, The Other Side of the Painting (Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2013), 23.

[13] Ginger Danto, The art of George Rodrigue (New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 2003), 25.

[14] Ibid., 25.

[15] Ibid., 25.

[16] Ibid., 25.

[17] Wendy W. Rodrigue, The Other Side of the Painting (Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2013), 27.

[18] Ibid., 27.

[19] Ginger Danto, The art of George Rodrigue (New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 2003), 24.

[20] Wendy W. Rodrigue, The Other Side of the Painting (Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2013), 23.

[21] Ibid., 31.

[22] Ibid., 44.

[23] Ibid., 43.

[24] Ibid., 44.

[25] Ibid., 44.

[26] Ibid., 44.

[27] Ibid., 44.

[28] Ibid., 44.

[29] George Rodrigue and Floyd Sommier, The Cajuns of George Rodrigue (Birmingham, Alabama: Oxmoor House, 1976), 35.

[30]Wendy W. Rodrigue, The Other Side of the Painting (Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2013), 64.

[31] Ibid., 64.

[32] George Rodrigue and Floyd Sommier, The Cajuns of George Rodrigue (Birmingham, Alabama: Oxmoor House, 1976), 4.

[33] Ibid., 5.

[34] Ibid., 14.

[35] Ginger Danto, The art of George Rodrigue (New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 2003), 25.

[36] Ibid., 25.

[37] George Rodrigue and Floyd Sommier, The Cajuns of George Rodrigue (Birmingham, Alabama: Oxmoor House, 1976), 27.

[38] Ibid., 27.

[39] Wendy W. Rodrigue, The Other Side of the Painting (Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2013), 64.

[40] Ibid., 66.

[41] Ibid., 64.

[42] George Rodrigue, Le Petit Cajun: Conversations with Andre Rodrigue, (Winter Park, Florida: Legacy Publishing, 1978), 7.

[43] Ibid., 7.

[44] Wendy W. Rodrigue, The Other Side of the Painting (Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2013), 91

[45] Ibid., 107.

[46] Ibid., 107.

[47] Ibid., 108.

[48] Ibid., 107.

[49] Ibid., 108.

[50] Ibid., 108.

[51] Ibid., 108.

[52] Ibid., 110.

[53] Ibid., 110.

[54] Ginger Danto, The art of George Rodrigue (New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 2003), 250.