Changes in clothing reveal aspects about the lives of the people who wore them and the time periods in which they lived. Unfortunately, most clothing from past centuries has decomposed due to poor storage procedures, over use, or conflict. This issue has made the study of costume history difficult for many historians; however, portraits are able to provide insight to popular dress of the past. This solution is directly related to dress from the Early American South since minimal garments exist from this region due to the environmental conditions, overuse, and the Civil War.

Fortunately, paintings can reveal how various political and social affiliations affected clothing design of Southerners from the time the colonists arrived in the late Sixteenth Century to the time America became a modern nation in the late Nineteenth Century. During colonial times in the South, there were seven different periods of dress: the Baroque period (1600-1700), the Rococo period (1700-1774), the Neoclassical inspired Directoire period (1774-1793) and Empire period (1793-1820), the Romantic period (1820-1849), the Crinoline period (1849-1869), and the Bustle period (1870-1889). Each of these eras had distinct style features, silhouettes, and textile designs that encouraged the textile industry to grow as social classes were kept in fashionable order. This exhibition offers an analysis of the attire found within portraits from the Early American South with the accompaniment of original or replicated garments from their time period. This project is intended to reveal how historical events impacted clothing in the early American South, and Southerners adapted to changes in the fashion industry.

I. Fashion Dolls

Most people would consider dolls to only have one main function- a children’s toy; however, from the Fifteenth to the late Eighteenth Century they were used to express the new styles of the time. The use of fashion dolls began in France during the Fifteenth Century and were passed from merchants to royal courts in order to display current fashions for men, women, and children[1]. The apparel for these dolls was finely constructed in the same meticulous manner as life size garments. This means these dolls had garments with linings, separate pockets, undergarments consisting of petticoats, and boned stays that were used to mold the women’s form into a cone shape and make her stand straight with her shoulders back[2]. The painstaking construction of dolls’ clothing reassures historians that they were used to transmit proper garment construction, which was very important to high society figures in the colonies. Since colonists were far from ateliers in Paris, having these dolls was the next best thing to being in Europe. Current styles would only take three months to transfer to the colonies, allowing high society in the colonies to stay fashion forward[3].

[1] Columbia University, Press. “Doll,” History Reference Center, EBSCOhost (2013)

[2] Linda Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America (2002) 29.

[3] Dr. Virginia Wimberly, “19th Century Wedding Dresses” (2014)

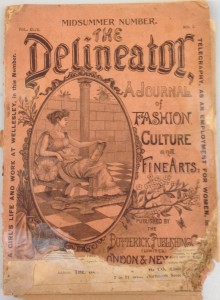

II. Fashion Magazines

By the end of the Eighteenth Century fashion magazines replaced fashion dolls for the transmission of changing styles because there was an increase in the interest in changing fashions[1]. This medium became essential for the fashion industry because it was a more economical and convenient way to inform the public on the most up-to-date garments. These magazines included illustrated accounts of French garments, garment suppliers, modern fashion reports, embroidery designs, paper patterns, and broad information articles that could be in color and black and white[2]. By the middle of the Nineteenth Century printing methods improved, costs of paper and taxation for periodicals were lowered, and literacy rates increased therefore allowing circulation to increase[3]. Due to the lowered cost of production, circulation increased and allowed people outside of the upper class to be aware of the trends in fashion and increase their knowledge of world fashion[4].

[1] Madeleine Ginsberg, “Fashion Magazines,” Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion (2005)

[2] Madeleine Ginsberg, “Fashion Magazines,” Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion (2005)

[3] Madeleine Ginsberg, “Fashion Magazines,” Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion (2005)

[4] “The High Tide of French Fashion.” Arts and Humanities Through the Eras, 5 (2005)

III. Baroque Period: 1600-mid 1700’s

Portrait of a Young Girl by Justus Engelhardt Kuhn, one of the first well-known portraitists from the southern colonies, displays many of characteristics of the Baroque style. Kuhn’s delicate style allowed him to create ornamented detail, a key aspect of the Baroque Period, which is represented through the precise drape and details of the child’s garment[1]. The Baroque style of art emphasized lavish ornamentation, free flowing lines and flat curved forms. The Baroque styles lead to the curvilinear form of garments in Europe and Colonial America from the end of the Sixteenth Century to the middle of the Nineteenth Century.

During this time children wore the same style of clothing as adults, since society viewed kids as little adults. In this painting the young girl is dressed in up-to-date clothing for this time period. This emphasized form-fitting long slender bodices with full skirts and sleeves that were in style until 1720. In the image of the mannequin, she is wearing a manteau that had a square neck corset bodice with a pronounced V at the waist, and was embellished with lace. The dress has ¾ length sleeves that have a full puff ending below the elbow, allowing layers of gathered lace fabric to be exposed. On top of her manteau is an apron with ornamental trim, and underneath she would be wearing a corset and a petticoat. Her skirt’s layers are supported though the use pannier frames located at her hips. The details of this dress reflect her family’s wealth since this garment was most likely created with professional tailors and used imported trim[2].

The similarities between Kuhn’s Portrait of a Young Girl and the garment from the Metropolitan Museum of Art are the structures of the garments they wear. Both of these garments have stomachers to emphasize slender waists, full skirts, square cut of the bodice, and ¾ length sleeves. Even though the child illustrated by Kuhn is dressed as little adult, one aspect of her outfit that distinguishes her as a child is the hanging fabric visible at her left shoulder that goes to her elbow[3]. Children who wore these hanging pieces of cloth were under the age of six, allowing viewers with an understanding of costume history to be aware of her age.

[1] Oliver Larkin, Art and Life in America (1960) 25.

[2] The information in this paragraph relies upon Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 251-291.

[3] Dr. Virginia Wimberly, The University of Alabama

IV. Rococo Period: mid 1700’s- 1800’s

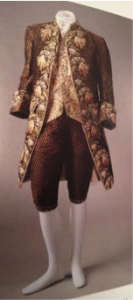

The portrait of Horatio Sharpe created by John Hesselius represents the typical dress and pose for a man of a high society from the Rococo Period. The portrait reveals his masculinity since his pose is “controlled and at ease”(Poesch, 79). Horatio Sharpe was involved in the military and was the governor of Maryland from 1753-1769[1]. In this portrait Horatio is wearing the latest fashion, which is illustrated by his narrow silhouette, stock, surtout (coat), waistcoat (vest), and breeches. After the mid Eighteenth Century, men’s silhouettes started narrowing. This occurs through the eradication of cravats, frockcoats, and waistcoats with full sleeves. The governor is wearing a surtout that ended below the knee that had cuffed sleeves and a narrow stand-up collar. The surtout was typically worn open to expose intricate waistcoats. During this time men’s waistcoats were the focal point of their attire, therefore brocaded and embroidered fabric was typically used. During the mid Eighteenth Century men wore stocks, which are similar to modern day ties, made from a white linen square “folded to form a high neckband that were stiffened with buckram and fastened behind the neck under a flat collar (Eubanks & Tortola, 276-275)”. Horatio is also wearing breeches that were closely fit and knee length.

[1] Jessie Poesch, The Art of the Old South (1989) 79.

V. Directoire Period: 1785-1800

During the Directoire period, silhouettes of fashion remained similar to ones from pre-Revolutionary period; however, they were becoming more simplistic. This trend can be seen through regency style dresses that are depicted on Martha Parke Custis and the mannequin. These dresses are influenced by Greek and Roman times, and were made from a lightweight cotton or linen[1]. Regency dresses had a tubular shape, and used a waistline placement under the breasts to shape the garment and gather it’s fullness. Some other elements of these dresses were they were floor length, had low cut square or round necklines, and could have short or long sleeves. A special aspect of both of these images have are their puffed sleeves. In order to obtain the “puffs” ties were used to section the sleeves allowing the wearer to decide their placement and amount[2].

An aspect of these garments that was most important to the people of the south was the technology that was used to make these cotton textiles. In 1794 the cotton gin was patented and changed the way cotton was produced in the American South. This machine was designed to separate cotton from its seed, making the crop more bountiful, and the fabric more affordable than ever. By 1820 the United States was producing 400,000 bales cotton a year, rising significantly from 3,000 bales in times before[3]. The majority of cotton produced came from the Deep South, where it was soon after exported to Great Britain, France, and New England and allowed for the development of new designs.

[1] Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 315.

[2] Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 316.

[3] Kevin Hillstrom and Laurie Collier Hillstrom, Slavery and the American South (2000) 7.

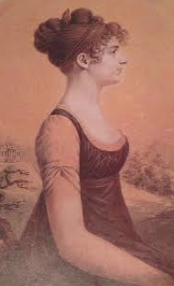

VI. Empire Period: 1799-1820

After the French Revolution women’s style changed drastically, the Baltimore native Harriet Rodgers exemplifies this look[1]. From 1799-1820 the Empire style was in effect, and it brought a Grecian influence to women’s clothing. During this period women’s dress created a tubular shape that was embodied by floor length Empire cut dresses. These garments had high waistlines that resided below the bosom with low round or square necklines, and had little or no sleeves. In order to maintain a Grecian feel they were made out of lightweight soft fabrics like linen and muslin. Since many of these garments were sheer a chemise and habit, a garment similar to bloomers, were worn underneath. The chemise was worn close to the body as possible and had a low square neckline that was cut full and straight down to the knees. Habits are short undershirts that were buttoned down the front and worn to contain women’s breasts. Since the look of narrow waists were out of style stays were implemented underneath clothing so women’s breasts could be pushed up and out[2].

[1] Jessie Poesch, The Art of the Old South (1989) 163.

[2] The information in this paragraph relies upon Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 251-291.

VII. Empire Period: 1799-1820

One outcome of the French Revolution was the division created between the colors used for men and women’s clothing. Men’s clothing during and after the Empire period had a somber feel due to their bland colors and lack of embellishment. The reason for this change in textiles was to bring uniformity to society and “emphasize the revolutionary idea of equality”(Eubanks and Tortora, 314). During this period there were slight changes in men’s dress, especially the design of the coat. Men’s coats, which were referred to as tail or cutaway coats, now ended at the waist and formed one or two tails that ended slightly above the knee. Another change that was made to men’s dress was the length and fit of pants. By 1807 breeches were being worn less, allowing long trousers and pantaloons to come into style. The difference between trousers and pantaloons is that pantaloons had a tighter fit. Men were also accessorizing with cravats and stocks. Cravats are large squares of fabric folded and wrapped around the neck, and stocks are stiffened neckbands that tied behind the neck. [1]In the portrait of John Speed Smith he is painted wearing a frock coat with one tail, a dress shirt with a ruffle, a waistcoat, a stock, pantaloons, and riding boots.

[1] The information in this paragraph relies upon Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 314-321.

VIII. The Romantic Period: 1820-1850

The Romantic period of dress was radically different than the Empire period. The styles of the Romantic period favored dress from the Middle Ages, which made silhouettes fuller and emphasized a smaller waist. During this time the most noticeable change was the size of sleeves that maintained fullness to the wrist or elbow. In the painting of Mrs. Pearce she is wearing demi-gigot sleeves that are full from the shoulder to the elbow then fitted to the wrist. The 1830’s costume displays gigot or leg-o-mutton sleeves that are full at the shoulder and gradually decrease in size to the wrist where they end in a fitted cuff. Another change in dress was the low set shoulder and lace pelerine that make it virtually impossible for women wearing these to do any kind of labor. Since lace machines were becoming more sophisticated the cost of this material was lowered, which allowed for the increased use of the lace pelerine’s wide cape-like collar. Romantic waistlines were located a few inches above the waist. Until 1833 waistlines were straight and accompanied by belts or sashes to emphasize the slender waist; however, after 1833 V shaped points were typically found at the waistline. Another trend of the Romantic was the size of the skirt that was becoming to grow wider and gradually shorter. In order to keep skirts full women wore multiple layers of petticoats and tied bustles around their waist that had a cotton filled pad in the back. From this point the size of skirts started growing. Mrs. Pearce and the mannequin are both shown with their hair in the style called a la Chinoise. Pulling back and side hair into a bun on top of the head, and curling the forehead and temple hairs formed this style.[1] Mrs. Pearce is also depicted wearing a pleated bonnet.

[1] The information in this paragraph relies upon Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 330-336.

IX: The Crinoline Period: 1850-1869

When ladies’ skirts started enlarging, they began hindering their independence since the weight of petticoat layers prevented them from easy movements and were uncomfortable. The styles of the Crinoline period took this assertion into effect and created a solution to the problem, which done through the invention of the cage crinoline leading to a more graceful appearance. This fixture was assembled with a succession of “whalebone or steel hoops that were sewn onto tapes to make a hoop skirt” (Eubanks & Tortora, 361). During the Crinoline period the shape of the hoop skirts varied, during the 1850’s they took on a full shape and during the 1860’s they became flatter in the front creating a pyramid shape.

In the images above the women are wearing evening dresses with full crinoline cages underneath. Their bodices consist of off the shoulder necklines that have a dip at the center and are supported by a wide bertha trim around the neckline. During this time the location of armhole seams changed and were located at the upper part of the arm. The image of the hoop dress displays bell-shaped sleeves, which are “narrow at the shoulder and gradually widened, ending between elbow and wrist” (Eubanks & Tortora, 363). Two major innovations that changed the clothing both of these ladies are wearing was the development of the first practical sewing machine in 1851, and synthetic coal tar dye that increased and intensified colored fabrics.[2]

During the second half of the Crinoline Period Civil War broke out in America, which halted the flow of imported and northern goods from entering the South. The embargo placed on the South during this time tried to restrict these people from keeping in touch with the outside world; however Southerners were able to keep up with the styles of the time since they would “do over” last seasons outfits. Women were forced to recycle pre-worn garments since textile manufacturers were located in the North, making Southerners unable to receive new fabrics and trims. Even though the South was restrained by a blockade, fashion magazines were able to find their way into the Mason Dixon months after their publication allowing women to stay in touch with fashions of Europe.[3]

[1] The information in this paragraph relies upon Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 354-365.

[2] The information in this paragraph relies upon Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 354-365.

[3] The information in this paragraph relies upon Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 356-357.

X. The Bustle Period: 1870-1900

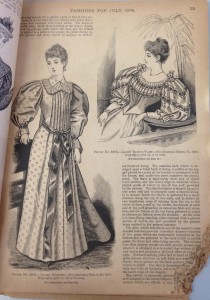

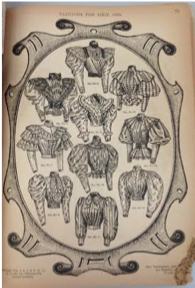

The Bustle Period received its name from the apparatus that was used to form popular silhouettes that created back fullness. This fashion period was marked by industrialization, women’s desire for dress reform, and revivals of historic styles. Industrialization allowed for garments to be produced on a large scale since cutting machines, sewing machines, textile production, and pattern pieces had improved. Due to these improvements clothing became mass-produced, and the fabric needed for skirt back fullness was inexpensively priced. Since women desired a change in dress, the cage crinoline was deserted by the 1870 and replaced with the bustle. The bustle gave added fullness to a women’s behind and even allowed them to ride a bike. During this period the size of the bustle varied, and was constructed in either half hoops of steel or cushion like devices[1].

The images above show popular styles of the Bustle Period. The photo of the daytime dress correlates to assertion of there being revivals of historic dress during this period. This dress gives the appearance of Medici collars of the 16th and 17th centuries, which stood up below the chin and used elaborate textiles; also, the dress is cut is in the polonaises style of the 18th century due to it’s tight bodice and skirt layers revealing the decorative underskirt. The daytime dress also exposes the popularity of the two-piece dress with matching skirt and basques, that has a corset shaping the bustline, waist, and smoothing round hip curves.[2]

The portrait by John Alexander White reveals a popular evening dress style of the late Bustle Period, which is refereed to as the Gay Nineties. During this time women’s figure took on the silhouette described as hourglass shaped. The hourglass shape was created through full cap sleeves, corsets, and wide bell shaped skirts that had pleating in the back. The design of this dress’ bodice was created with a low round neck neckline and off that shoulder lines that was common after 1893. The woman is also wearing large balloon shaped sleeves that ended below the elbow.[3]

[1] The information in this paragraph relies upon Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 379-386.

[2] The information in this paragraph relies upon Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 383-387.

[3] The information in this paragraph relies upon Keith Eubanks & Phyllis Tortora, Survey of Historic Costumes (2010) 396-400.

Works Cited

Baumgarten, Linda. . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Collier Hillstrom, Laurie, and Hillstrom, Kevin. “Slavery and the American South.” Ed. Lawrence W. Baker. Vol. 3: Almanac. Detroit: UXL, 2000. 1-14. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 10 Jan. 2015

“Columbia University, Press. “Doll.” Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition (September 2013): 1. History Reference Center, EBSCOhost (accessed April 12, 2014).

Dickson, Harold. Arts of the Young Republic. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1968.

Eubanks, Keith, and Phyllis Tortora. Survey of Historic Costume. 5. Edited by Olga Kontzias. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010.

Ginsberg, Madeleine. “Fashion Magazines.” Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion. Ed. Valerie Steele. Vol. 2. Detroit: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2005. 54-56. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 12 Apr. 2014.

Larkin, Oliver. Art and Life in America. Canada: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1949

Poesch, Jessie. The Art of the Old South. New York: Harrison House, 1989.

Russell, Douglas. Costume History and Style. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1983. The American Art Book. London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1999.

Wimberly, Virginia. “19th Century Wedding Dresses” (Paper presented for the Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, April 10, 2014.

“The High Tide of French Fashion.” Arts and Humanities Through the Eras. Ed. Edward I. Bleiberg, James Allan Evans, Kristen Mossler Figg, Philip M. Soergel, and John Block Friedman. Vol. 5: The Age of the Baroque and Enlightenment 1600-1800. Detroit: Gale, 2005. 128-33. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 12 Apr. 2014.