Death, dying, and the deceased has been an inspiration for artists and their patrons since antiquity forward. From morbidly memorialized martyred saints and heroes, to the Medieval obsession with “memento mori”, the subject matter falls in an out of trend through time. Early America was no stranger to this obsession with death. The American South was a dangerous place to live, even for the very wealthy. Sickness swept over the land seemingly without cause. Medical supplies and trained doctors were scarce. The American posthumous mourning portrait arrived as a means for families to deal with the grief of losing a loved one.[i] Sadly, as children fell more deeply ill more often than their elders mourning portraits more frequently depict children and adolescents.[ii]

Posthumous portraiture was not invented in America, but the style was adapted to suit the American patron’s stylistic preferences. These mourning portraits were often painted in a distinguishable style with easily recognizable symbolism. For the large-scale style of portrait the “sitter” is often shown as seated or standing and looks very much alive and well. Rosy dimpled cheeks often usher in a slight smile and a glimmering eye. The patrons would have wished to remember the sitter at their very healthiest moments, and often worked hand in hand with the artist to make sure that the work was the perfect homage to the sitter.[iii]

Posthumous portraiture was most popular in America during the nineteenth century. The drive behind the patronage came from complex mourning rituals that are quite different from modern funerals. As access to funeral homes was not always possible close contact with the deceased was the norm. The family was responsible for washing, dressing, and the laying out of the body before the funeral. The body was watched over from its preparation for the burial. Adornment with flowers and fine clothing would not have been unusual and people in the community would stop by to pay their respects to the deceased before transportation to the body’s final resting place. Death was certainly a tangible part of society.[iv]

Portraits completed after a death were most often commissioned during the mourning period. Sketching straight from the corpse was done when an artist was readily available, even taking measurements straight from the corpse. If the commission was filled after the burial, the artist would be adapted from pre-existing daguerreotypes, sketched from an earlier portrait, or potentially even modeled from family members with similar features. [v]

The posthumous portrait was adopted from European traditions of portraying the dead as alive, but Americans adapted it to suit their own mourning custom.[vi] These posthumous portraits became a genre all their own by transforming the dead back into life through this medium. This was part of the daily lives of many artists, and artists would have fashioned these works to draw attention to the sitter’s deceased status.[vii]

Unknown Child Holding Doll and Shoe, Attributed to George G. Hartwell (1815–1901), Probably Massachusetts or Maine c. 1845, Oil on canvas, 26 3/4 x 21 3/4 in. American Folk Art Museum

This portrait of an unidentified child features a myriad of symbolism that would have been understood by the viewer to indicate that the child was deceased. The departing ship in the background, the dead tree with a cluster of grapes and roses were all recognizable parts of the iconography. It has also been argued that the depiction of a child with one shoe off would indicate the child is departed from the world as well, but some argue that the motif only shows a transition from infancy to becoming a toddler. As with living portraits we can use iconographical cues to suggest the sex of the child. Here we see the infant playing with dolls, suggesting the toddler is a female. This particular portrait was probably painted by George G. Hartwell, as he lived in Boston when this painting was produced and resembles his more primitive folksy style. [viii]

Another way to recognize a portrait as posthumous is to look at the clothing and colors used in the painting. While Ralph E.W. Earl painted pictures of Rachel Jackson while she was alive, this particular portrait is dated three years after her death. One could presume this was produced as a gift to Andrew Jackson to ease the heartache of his loss. While we already know this was painted after her death, the audience at the time would have been able to see this was posthumous through the use of red, white, and black and the rose in her hand. While not always possible, the black mourning clothes in combination with the other symbolism make this a clear posthumous portrait. [ix]

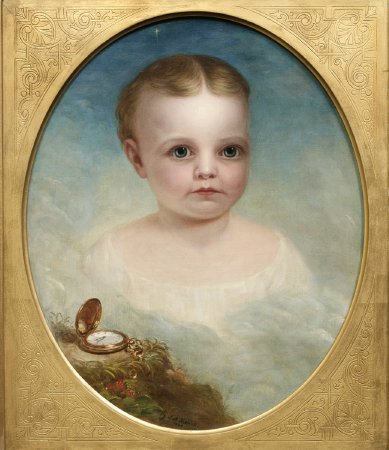

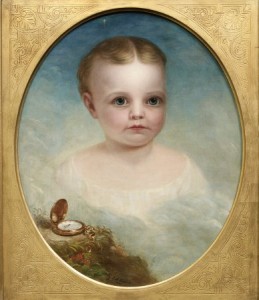

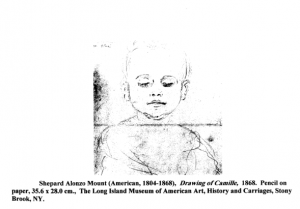

Shepard Alonzo Mount (1804-1868), Portrait of Camille Mount, 1868, Oil on canvas, Long Island Museum of American Art, Gift of the Estate of Dorothy deBevoise Mount, 1959

A black and red color scheme isn’t always used in rendering a posthumous portrait. The artist’s granddaughter is shown calmly floating above a stopped clock. We know from a letter to his son that the child was deceased when the portrait was painted. [x]

Mount writes,

“Telling you of Joshua and Edna . . . they have lost their little Camille – she is dead – the sweet beautiful babe is dead. She died from the effects of teething. It so happened – Providentely [sic] I thought – that I was in Glen Cove – and for two or three days before she died I made several drawings of her which enabled me, as soon as She was buried to commence a portrait of her and in 7 days I succeeded in finishing one of the best portraits of a child that I have ever painted.” [xi]

Phoebe Lloyd mentions the drawings he had taken of her had marks where calipers had been used to measure the child’s head to get the perfect measurements. [xii]

Phoebe Lloyd mentions the drawings he had taken of her had marks where calipers had been used to measure the child’s head to get the perfect measurements. [xii]

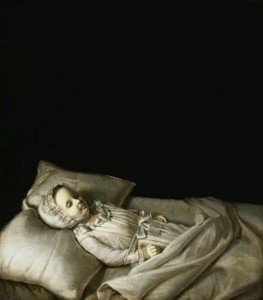

Rachel Weeping Enlarged in 1776; repainted in 1818 Charles Willson Peale, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art. 1741 – 1827

Rachel Weeping Enlarged in 1776; repainted in 1818 Charles Willson Peale, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art. 1741 – 1827

In 1776, Charles Willson Peale who was the patriarch of Philadelphia family of artists, released this posthumous mourning painting titled Rachel Weeping, to the public. Peale’s wife originally commissioned the painting as a private memento after the death of their young daughter. At first the work only featured the daughter, but upon releasing to the public he expanded the picture to include his wife seated over their deceased child.[xiii] Similar imagery became more popular with the advent of photography.[xiv]

The red, white, and black color scheme signals that this may be a posthumous portrait. While there is no documentation proving such, I would suggest that the pose with the rocking horse may hearken back to ancient iconography that the artist would have been aware of from her father Charles Willson Peale’s art collection. There is a long history of honoring deceased military leaders by depicting them “adventus”, or shown victorious returning from battle a lot upon a horse. While, the rocking horse is no great steed, it is certainly reminiscent of this ancient imperial style. [xv]

The portrait of Sarah Louise Spense ,1833, by Ralph E.W. Earle, in the collection of Craig and Tarlton, Inc, Raleigh, North Carolina

In this work the subject appears alive and well, and only a few clues lead us to believe this is work is posthumous. She stands with a relaxed posture holding her hat in her left hand and a down turned flower in the right. A letter attached to the back of the painting lets us know that Sarah Louise was deceased. It has been reported that Earle had taken measurements from her corpse, in addition to a lock of her hair as well as referencing an earlier portrait to get her features just right. Sarah’s half sister also posed for Earle as she had a similar complexion and eye shape. The simple down turned rose is the only identifiable symbol of death.[xvi]

Unknown Artist, Memorial to Nicholas M. S. Catlin c. 1852, oil on canvas, 98.4 x 73.2 cm in the collection of The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Identifying this as a posthumous portrait is easier than some of the previous works. This painting contains roses again, white, red, and black, and an obelisk. A boat sails on the horizon symbolizing the passage from life to death. [xvii] The weeping willow is a symbol that was used on tombstones at the time and the artist fittingly utilizes it here. [xviii]

Thomas Coram was not known for portraits, and this work would have likely been a gift to Charles Glover. Inscription reads “beloved departed wife- from his friends”. The small size would have lent to the precious nature of the work. As there is no noticeable iconography, it may not have been a direct likeness. [xix]

The posthumous portrait can be hard to identify. Often, the only true way to know that the sitter is deceased is the inscription on the back. For avenues of further study I would look for more unifying themes in the subject matter. There is little regarding information on the symbolism and especially little on how it would have been perceived by the public. There portraits are a unique representation of the patrons wishes and the artists style.

Works Cited

Lloyd, Phoebe. “Posthumous Portraits of Children in Nineteenth-century America.” Social Science 71, no. 1 (1986): 32-38.

“American Folk Art Museum.” American Folk Art Museum. http://www.folkartmuseum.org/?t=images&id=1589 (accessed April 15, 2014).

Retford, Kate. A Death in the Family: Posthumous Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century England. New York: Association of Art Historians, 2010.

The Museums at Stony Brook. “Is Art Hereditary? The Mounts, A Family of Painters.” Is Art Hereditary? The Mounts, A Family of Painters. http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/2aa/2aa622.htm (accessed April 15, 2014).

Lloyd, Phoebe. “A Death in the Family.”Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin” Vol. 78, no. 335 (1982): 2-13.

Schorsch, Anita. “Mourning Art: A Neoclassical Reflection in America.” American Art Journal 8 (1976): 4-15.

Huneault, Kristina. “Aspects of Acceptance and Denial in Painted Posthumous Portraits and Postmortem Photographs of Nineteenth-Century Children.” Ottowa: Concordia University Libraries, 2011.

Kete, Mary Louise. Sentimental Collaborations: Mourning and Middle-class Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.

Stephens, Rachel “Art of the American South Chapter 6” Art of the American South. University of Alabama. [April 4th 2014]

Endnotes

[i] Mary Louise Kete, Sentimental Collaborations: Mourning and Middle-class Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. (Durham: Duke University Press 2000).

[ii] Phoebe Lloyd, Posthumous Portraits of Children in Nineteenth-century America. (Social Science; 1986) 32-38.

[iii] Phoebe Lloyd, Posthumous Portraits of Children in Nineteenth-century America. (Social Science; 1986) 32-38.

[iv]Mary Louise Kete, Sentimental Collaborations: Mourning and Middle-class Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. (Durham: Duke University Press 2000).

[v] Phoebe Lloyd, Posthumous Portraits of Children in Nineteenth-century America. (Social Science; 1986) 32-38.

[vi] Kate Retford, A Death in the Family: Posthumous Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century England, (New York: Association of Art Historians, 2010).

[vii]Phoebe Lloyd, Posthumous Portraits of Children in Nineteenth-century America. (Social Science; 1986) 32-38.

[viii] “American Folk Art Museum.” American Folk Art Museum. http://www.folkartmuseum.org/?t=images&id=1589 (accessed April 15, 2014).

[ix] Phoebe Lloyd, Posthumous Portraits of Children in Nineteenth-century America. (Social Science; 1986) 32-38.

[x] Phoebe Lloyd, Posthumous Portraits of Children in Nineteenth-century America. (Social Science; 1986) 32-38.

[xi] The Museums at Stony Brook. “Is Art Hereditary? The Mounts, A Family of Painters.” Is Art Hereditary? The Mounts, A Family of Painters. http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/2aa/2aa622.htm (accessed April 15, 2014).

[xii] Phoebe Lloyd, Posthumous Portraits of Children in Nineteenth-century America. (Social Science; 1986) 32-38.

[xiii] Phoebe Lloyd, “A Death in the Family.”Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin” ( Philadelphia: 1982) 2-13.

[xiv] Mary Louise Kete, Sentimental Collaborations: Mourning and Middle-class Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. (Durham: Duke University Press 2000).

[xv] Anita Schorsch, “Mourning Art: A Neoclassical Reflection in America.” (American Art Journal: 1976) 4-15.

[xvi] Phoebe Lloyd, “A Death in the Family.”Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin” ( Philadelphia: 1982) 2-13.

[xvii] Phoebe Lloyd, “A Death in the Family.”Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin” ( Philadelphia: 1982) 2-13.

[xviii] Mary Louise Kete, Sentimental Collaborations: Mourning and Middle-class Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. (Durham: Duke University Press 2000).

[xviiii] Stephens, Rachel “Art of the American South Chapter 6” Art of the American South. University of Alabama. [April 4th 2014]