Until the mid-eighteenth century, scientific illustration in America was limited, if not virtually non-existent. This all changed when British born naturalist, Mark Catesby, became the first to illustrate a widespread collection of plants and animals in America. Catesby became well known throughout Europe and America after his publication of Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands. His publication remained the most paramount collection of scientific illustrations for nearly a century. [1]

Catesby (1682-1749) was born to a renowned family in Essex, England, where he was also raised and schooled. Catesby had a particular interest in botany and natural history from a young age. Wealth on his mother’s side allowed him to frequent Castle Hedingham as a young boy, where his maternal grandfather had his own botanical garden. Family ties were influential in Catesby’s success as a naturalist. Had it not been for his sister’s move to Virginia, it is unlikely Catesby would have found himself in the New World. Catesby joined his sister Elizabeth and husband Dr. William Cocke in Williamsburg in April of 1712. Thus began his first adventure in the New World. Shortly after his arrival, Catesby met council member and aspiring naturalist William Byrd. The two formed a lasting friendship and Byrd ultimately introduced Catesby to the flora and fauna of Virginia that brought him fame. [2]

During this first voyage to the New World however, Catesby spent the majority of his time collecting specimens to ship back to England. The shipments made their way to privileged natural historians of London, consequently earning Catesby a name for himself among them. After seven years spent exploring the New World, Catesby returned to England. In England Catesby had gained supporters, some of which were eager to support his interests financially. This was motivation enough for Catesby to return to American just three short years later with a new mission: to assemble an inclusive collection of America’s natural history. It is then that Mark Catesby began to work on his drawings that would later set the standard for naturalists to come.

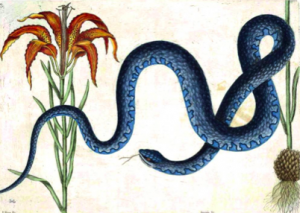

South Carolina was the destination of Catesby’s second trek to the Americas. It was there that he, presumably, encountered the Wampum Snake.

Catesby illustrated the Wampum Snake alongside the Red Lily, in his Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands. Both species are known to be native of the Carolinas. Catesby habitually depicted both flora and fauna together in one illustration. The naturalist, in all probability did so to exhibit how different species might co-habit in the Americas. Catesby served as a natural history informant to his patrons in England; he worked diligently on his illustrations but continued to send specimens over seas nonetheless. In fact, it was not unusual for him to ship snakes among other small creatures to England by placing them in jars filled with rum. Occasionally, the rum proved to be far too tempting for the crewmen on merchant ships-regardless of whatever creature was held in the jar with it. Needless to say, not all specimens made it back to their corresponding collectors. [3]

The New World’s array of birds intrigued Mark Catesby. His illustration of the Blew Gros-beak is perhaps one of his most well known works today.

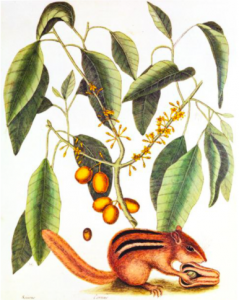

The Blue Grosbeak is shown perched atop the branch of what Catesby labels as Magnolia Lauri folio, beak open in anticipation of a falling sweet bay seed. The coupling of this particular bird with this particular seed was all but coincidental. Catesby was known to dissect birds and study the inside of their intestines in order to more adequately select which plants or berries to draw beside them. When shipping birds overseas, Catesby chose to bake them in an oven before stuffing and covering them with tobacco powder. This is to say that containing creatures in jars filled with rum was not Mark Catesby’s only unconventional treatment of specimens for the sake of his work. Such measures would centuries later be adopted by naturalists influenced by Catesby.

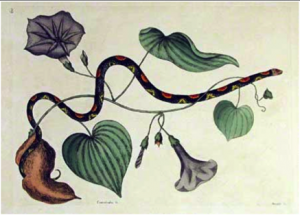

While Catesby lacked formal training as an artist, his purpose was to articulate American nature to the British through his illustrations. As the colonies emerged, interest in the New World catapulted in England. His conscious effort to pair flora and fauna and do so according to life made his work an authentic source for those who could not experience it first hand. American art curator, Amy Meyers, best described it saying, “Mark Catesby helped advance what much later became the science of ecology- the interactions of living things in nature”. His piece Bead Snake With Sweet Potato proved that humans were not exempt from involvement in these interactions. Farmers in Virginia dug up this type of snake when harvesting their sweet potatoes.

A common dynamic shown in Catesby’s work is the portrayal of vivacity in the fauna. The Eastern Chipmunk with Mastick tree is subject to this dynamic, illustrating a truthful moment in the day to day life of a chipmunk: consumption of a nut.

The flicking tongue of a snake, or the open beak of a bird seen in Catesby drawings document this dynamic as well. This dynamic was of particular importance for Catesby’s British audience. His illustrations satisfied the function of faithful representation in a time when photographs did not yet exist.

Despite all indications of Catesby being a naturalist pioneer, his fame after the eighteenth century subsided substantially. The next century brought a new naturalist into the limelight: John James Audubon. Consequently, Catesby would perpetually remain in the shadow of Audubon. Perhaps Catesby’s lack of formal training was to blame for this shift- he himself was aware he lacked skill in perspective. Whatever the reason, it is certain that Catesby was an influential factor in Audubon’s work in more ways than one.

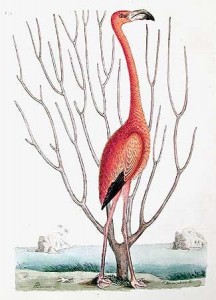

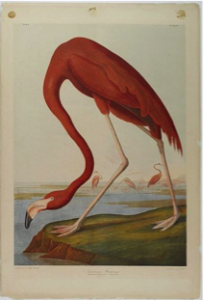

The bizarre measures Catesby took to ensure the authenticity of his illustrations launched him to pioneer status. The dissection of birds to discover which plants to pair with each species was eccentric, but ingenious at the time nonetheless. And while often times Catesby killed and took apart his subjects, he avoided such extreme measure whenever possible. Catesby attempted to keep that portrayal of vivacity at the cost of the aesthetic appeal of his work. His Flamingo, although far from realistic in style, is upright and poised, as one would expect of the elegant bird.

Audubon adopted Catesby’s use of animal sacrifice for the sake of art, only much more aggressively. Audubon mercilessly- and at times savagely killed his subjects before painting them. He used hidden wires to pose the animals, giving him more control when painting his subjects. In addition to gaining control, Audubon gained time to execute his work by not having to paint from memory in the case that the animal should move. In comparison to Catesby’s flamingo, Audubon’s, while perhaps more aesthetically pleasing, looks limp and lifeless.

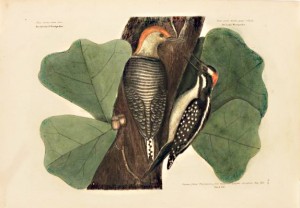

Aside from inspiring the manipulation of subjects, Catesby played a role in influencing Audubon’s works compositionally. Ventro Rubro displays the interaction between species Catesby captures so well, yet it is a rarity in that the interaction is between two members of the same species. The birds become the subject while the flora serves a dual purpose- documentation, as well as a background.

Much of Audubon’s success came from illustrating his subjects in a relevant background. Even as Audubon’s backgrounds are more developed than Catesby’s, it was typical for naturalists to exclude a background when illustrating for the purpose of documentation. As a matter of fact, Catesby was the first to draw birds against a botanical background.[4] Clearly, Catesby was an influence to Audubon in that matter. Additionally, Audubon’s Mourning Dove emulates the interaction between the two birds Catesby’s Ventro Rubro.

Like Ventro Rubro, Bobolinks is a rare example of Catesby using two of the same species in a single composition. Through the creation of Bobolinks, Catesby uncovered that these birds migrated from Cuba to South Carolina to follow rice as it ripened.

Colonists had previously imagined that the birds hid in the bottom of mud each year in order to hibernate. [5]Were it not for Catesby, the colonists may have never known. Thus his work was an influence even to those who knew nothing of natural history.

Mark Catesby was extraordinary in that he was incredibly self-reliant. With no formal training he managed to become a renowned naturalist, eventually molding the most renowned naturalist to date. Upon learning his illustrations would have to be transferred to copper in order to be printed, Catesby yet again demonstrated unwavering self-reliance. To diminish costs, Catesby learned to etch and managed to produce 220 plates[6], including the hand colored Summer Duck.

Though some etchings were noticeably flawed, Catesby’s ability to produce A Natural History with such little help is undoubtedly admirable.

Upon release, the queen of Sweden, the princess of Wales, and range of nobles purchased A Natural History across Europe. This was however, his only successful publication. Catesby may have faded into obscurity during his later years, but his work will evermore remain a lasting influence in the world of Natural History and art.

Catesby, Mark. Catesby’s Birds of Colonial America, Edited by Alan Feduccia. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1985.

Audubon, John James. Audubon’s Birds of America, Edited by Ludlow Griscom. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1950.

Wilson, David. “The Iconography of Mark Catesby.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 4, no. 2 (1970-1971): 169-183. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2737674

Yih, David. “Mark Catesby: Pioneering Naturalist, Artist, and Horticulturist.” Arnoldia 70, no. 3 (2013): 25-36. http://arnoldia.arboretum.harvard.edu/pdf/articles/2013-70-3-mark-catesby-pioneering-naturalist-artist-and-horticulturist.pdf

Frick, George Frederick and Raymond Phineas Stearns. Mark Catesby: The Colonial Audubon. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1961.

Meyers, Amy R. and Margaret Beck Pritchard. Empire’s Nature: Mark Catesby’s New World Vision. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Stewart, Doug. “Mark Catesby.” Smithsonian 28, no. 6 (1997): 96. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.libdata.lib.ua.edu/ehost/detail?vid=3&sid=e368f2a6-5388-4f9c-afbc-486dcbf8fb1f%40sessionmgr115&hid=115&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=aph&AN=9709036128

[1] Mark Catesby, Catesby’s Birds of Colonial America, Edited by Alan Feduccia. (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1985), Preface.

[2] Mark Catesby, Catesby’s Birds of Colonial America, Edited by Alan Feduccia. (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 3.

[3] Doug Stewart, “Mark Catesby.” Smithsonian 28, no. 6 (1997): 96.

[4] David Yih, “Mark Catesby: Pioneering Naturalist, Artist, and Horticulturist.” Arnoldia 70, no. 3 (2013): 33.

[5] Doug Stewart, “Mark Catesby.” Smithsonian 28, no. 6 (1997): 96.

[6] David Yih, “Mark Catesby: Pioneering Naturalist, Artist, and Horticulturist.” Arnoldia 70, no. 3 (2013): 33.

Pingback: Mark Catesby : arte e scienza | controappuntoblog.org