Southerners tend to have a unique perspective on their cultural history, particularly when it comes to their view the Old South. Its legend is surrounded by nostalgia and sentiment, mixed with a certain longing for an idealized past that may have never truly existed. The most prominent examples of this romanticized version of the Old South exist in southern art, of which portraiture was the most popular amongst the middle classes. Not only were portraits decorative objects for the home, but they were also considered to be important family heirlooms and commemorative objects. What is known today about southern fashion and family history is largely due to the popularity of portraits. Most artists were itinerant, traveling from city to city in search of commissions. One of the most well-known itinerant portrait artists of his time was Jean Joseph Vaudechamp (1790-1864), a native of France who painted in New Orleans during the 1830s. In 1811 he began his training in Paris with Anne-Louis Girodet at the age of twenty. Not only was Girodet one of the most well-respected artists in Paris at the time, but while working in his studio the young Vaudechamp would have had access to many examples of classical drawings and paintings, as well as literature from antiquity. Although he was able to make a name for himself by displaying his work in many of the Parisian salons, he lived constantly in the shadows of his master. At the age of forty-one he traveled to the city of New Orleans, Louisiana to “seek his fortune abroad.” Vaudechamp set up a studio in what is today known as the French Quarter and spent the next ten years traveling back and forth between the United States and France, spending the winter months in New Orleans painting portraits of the local elite. His subjects were mostly Creoles, or the citizens of the city who identified themselves as French rather than American, and in fact had a rather tense relationship with their American rivals. These portraits were usually painted in the neoclassical style with the half-length sitter against a plain, olive and brown colored background. His male subjects were usually placed higher in the picture frame in order to give them a more dignified, authoritative look. Females, on the other hand, were made to look more personable while still retaining neoclassical qualities like elongated necks and modest dress. Both his male and female types were most certainly borrowed from his old master. Vaudechamp showed great attention to details, especially in the features of his sitters, which resulted in very realistic likenesses of his patrons. His portraits accurately convey the sitters’ personalities, making them more believable renderings of Creole culture than any of the other French-born artists in New Orleans were able to accomplish. Vaudechamp’s ability to render the self-contained nature of his Creole sitters and paint them in such a way that, through portraiture, they could de-Americanize themselves, made him the most popular portrait painter in New Orleans.

Portrait of a Woman with a Fur Boa, Jean-Joseph Vaudechamp, 1832, The Historic New Orleans Collection

This portrait of an unidentified woman exemplifies Vaudechamp’s composition for female sitters: bust-length view, elaborate hair and clothing styled after Parisian fashion, and the typical vague background used in most of his portraits. This particular composition was repeated at least two other times almost exactly, including similar hairstyles and the same boa.

Madame Bailly Blanchard was the wife of a commission merchant whose home was in the old section of the city. Vaudechamp took a great deal of care to render his elderly female sitters, acknowledging their age yet still respectfully capturing their individual personalities. Here, he depicts her grimacing smile just as delicately as the eyeglasses she holds. Five years after the completion of this portrait, Vaudechamp was approached by her children in Paris and asked to paint their portraits as well.

William Charles Cole Claiborne II, Jean Joseph Vaudechamp, 1831, The Historic New Orleans Collection

William Charles Cole Claiborne II was the son of William Charles Cole Claiborne, who was the first governor of the Louisiana Territory and had a lucrative career in politics throughout his life. Scholars believe that, like Vaudechamp and his teacher Girodet, Claiborne II lived in the shadows of his father’s success and his dependency on his father’s reputation and wealth represents the next generation of Louisiana men. Perhaps ironically though the composition of this portrait was copied almost exactly from Girodet’s Portrait of an Indian, with the horizon line low in the picture plane and a dark, cloudy sky as the background.

Antoine Jaques Phillipe de Marigny de Mandeville, Jean Joseph Vaudechamp, 1833, Louisiana State Museum

Mandeville de Marigny, as he was mostly called, came from one of the oldest Louisiana families. His father was a wealthy landowner and had many important political connections, including a friendship with the King of France. Mandeville himself studied at St. Cyr Academy in France and served in the French Army. When he returned to New Orleans he became a lieutenant in the Louisiana Militia and is shown in the dress uniform for the First Squadron of Cavalry, Orleans Lancers. Later in his life he served as a colonel in the Confederate Army.

Not much is known about this portrait of an unnamed child. Vaudechamp had a special gift for painting children and capturing their personalities, despite their young age. This might be due to the fact that he had three children of his own. In this portrait, special attention was paid to the child’s dark eyes and her fair skin, carefully painted so as not to look too similar to the painted porcelain of the doll she holds in her lap.

Elmire Olivier de Vezin (Madame Furcy Verret), Jean Joseph Vaudechamp, 1836, The Historic New Orleans Collection

The de Vezin family was once a prominent French family in New Orleans. Elmire was the daughter of Nicolas Joseph Godfroi Oliver de Vezin; she eventually married Furcy Verret. This portrait is a copy of another portrait completed fourteen years earlier by Louis Antoine Collas when Elmire was twenty-five years old. In his version, Vaudechamp kept the same composition yet made the painting his own by detailing the lace on her dress and her earrings.

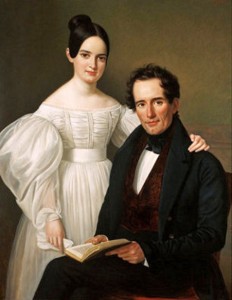

Edmond Jean Forstall and his daughter Desiree Forstall (later Madame Charles Roman), Jean Joseph Vaudechamp, 1836, The Historic New Orleans Collection

Clara Durel, Madame Edmond Jean Forstall and her son Eugene Forstall, Jean Joseph Vaudechamp, 1836, The Historic New Orleans Collection

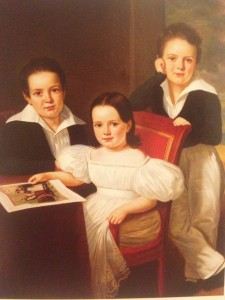

Victor Forstall, Ernest Forstall, and Eugenie Forstall, Jean Joseph Vaudechamp, 1836, Private Collection

The Forstall family was one of the wealthiest and most prominent families in New Orleans. They traced their lineage back to the twelfth century in England and their motto read “Into the hearts of the King’s enemies.” Edmond Jean Forstall was the president of the New Orleans Sugar Refinery. He married Clara Durel and together they produced nine children. Although it was rare for Vaudechamp to paint such large, detailed portraits with multiple sitters, he made exceptions for families with wealth and prominence such as the Forstalls, especially since the prestige of their portraits helped cement his career in New Orleans. The double portraits adhere to the tradition of women being seated on the left and men on the right. In her portrait with her son Eugene, Clara holds a miniature of her husband in her hand.

Jean Baptiste Plauche married Mathilde St. Amant of St. Charles Parish and together they had seven children. He ranked very high in the military in Louisiana and was best known for his efforts at the Battle of New Orleans, where he led the “Famous Battalion d’Orleans” to a victory over the English. In 1850 he served as the lieutenant-governor of Louisiana. He died in 1858 at the age of seventy-five. Because of his family’s prominence in society, his portrait is considered to be on par with that of the Forstall commissions.

It seems that after 1839 Vaudechamp did not return to Louisiana but continued to paint in Paris, although he was not nearly as popular in France. In fact, after he died his art fell mostly into obscurity and although he was buried there, no one knows the exact location of his grave. Even more surprising, however, is how little literature exists about Vaudechamp in books or journals about southern artists. Although he is a recognized name, relatively little research has been done on the majority of his portraits. Seventy-eight portraits by Vaudechamp have been located, but it is widely believed that there are many more in existence. There was a lucrative market in New Orleans for portraits painted by European artists, and the success of Vaudechamp’s paintings of the Creole elite reveal their need to hold on to a previously established status and way of life, not unlike the modern need to cling to the romantic nostalgia associated with the Old South. Arguably, Vaudechamp’s portraits have helped shape our view of the upper class members of the Old South.

Bibliography

Bonner, Judith H. “Paintings from the Permanent Collection of the Historic New Orleans Collection,” in Complementary Visions of Louisiana Art, edited by Patricia Brady, Louise C. Hoffman, and Lynn D. Adams, 64. New Orleans: The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1996.

Mahe II, John A., and Rosanne McCaffrey, ed. Encyclopedia of New Orleans Artists 1718-1918. New Orleans: The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1987.

Pennington, Estill Curtis. Downriver: Currents of Style in Louisiana Painting, 1800-1950. Gretna: Pelican Publishing Inc., 1991.

Pennington, Estill Curtis. Look Away: Reality and Sentiment in Southern Art. Spartanburg: Peachtree Publishers, Ltd., 1989.

Poesch, Jessie. The Art of the Old South. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1983.

Rudolph, William Keyse. Vaudechamp in New Orleans. New Orleans: The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2007.

Seebold, Herman de Bachelle. Old Louisiana Plantation Homes and Family Trees. New Orleans: Pelican Press, Inc., 1941.